Kyla Fahy, Adam Jadwin-Gavin, Liam Judd, and Ethan Post

Overview

The purpose of this paper is to discuss and analyze the effects that a crisis has on consumer behavior. We will be doing this by analyzing the impacts of terrorism, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the 2008 financial crisis. Here we have 4 shocks with differing causes and forms of severity. We will analyze how each of these shocks are similar but also differ through severity, length, and impact on the consumer both physically and psychologically. Periods of crisis affect consumer behavior, however, findings show that economic impacts have a short lifespan while psychological impacts, such as perception of future crises or spending habits have a longer-lasting effect.

Introduction

Consumer behavior is often dictated by the surrounding environment, as well as the personal needs and wants of the consumer. When a given consumer’s society and economy are in a neutral state, it can be expected that the consumer will act with little external influence, and will be more true to their personal needs. Decision making in consumers is largely constrained by emotions and limitations of human information processing, with economic decisions being affected by feelings and sentiments, motives, attitudes, social influence and heuristics in information processing (Kirchler & Hoelzl, 2011). During the event of an economic crisis, pandemic, or terrorist attack, it can be assumed there will be alterations in consumer behavior as these events will trigger a change in motives and feelings within the consumer. These consumer-behavior altering crises include terrorism, widespread disease, war and economic recessions.

War

One of the crises that alters consumer-behavioral outcomes is foreign and domestic wars. In the case of a consumer’s home country going to war with a foreign adversary, nationalism is likely to increase within the consumer as a means of supporting their immediate community. This is apparent when analyzing consumer behavior within the United States during the U.S. – Iraq war from 2003 – 2011, where the weekly market share of American brands grew in fallen soldiers’ U.S. hometowns (Helms et. al., 2022). Helms and colleagues analyzed weekly supermarket sales for a nationally representative sample of more than 8,000 brands in over 1,100 U.S. supermarkets, with the researchers hypothesis stating that “local casualties increase growth in American brands’ market share in local supermarkets”. A local casualty is defined as the death in that week of an American soldier whose hometown is located in the same county as the store. Once results were obtained and synthesized, it was found that the researcher’s hypothesis was correct as when local news within a county dispatched information regarding the recent death of a local U.S. veteran who died in Iraq, the local consumers would often turn to American brands within the supermarket as consumers reaffirm their national identity in response to external threat. While American consumers may have increased their consumption of American brands in support of local veterans during the U.S. – Iraq war, there was also a boycotting of French wine in America during the war as the government of France was openly against the United States involvement with Iraq. American consumers were able to comfortably halt consumption of French wine, as within the United States are several substitute products for French wine, many of which are variations of wine manufactured and produced either in American or other countries. A study conducted measuring the magnitude of consumers’ participation in the boycott of French wine during the U.S. – Iraq war found “numerous substitutes for French wine, and for at least some French wine, there are close substitutes from other countries. Hence, the sacrifice a consumer incurs by altering their purchase decision is likely to be minor” (Chavis & Leslie, 2006). Consumers are more easily able to boycott products from hostile nations when the consumer is not dependent on the product and when there are available substitutes for consumption. If the consumer is dependent on the product and there are no available substitutes or alternatives, then it will be much more difficult and much less likely for the consumer to boycott the product.

Consumer animosity towards a rival nation can also alter behavior, especially if the rival nation is at war with the consumer’s home nation. Geopolitical tensions between Russia and Ukraine erupted after the Ukrainian revolution for dignity in 2014, culminating in Russia’s invasion in 2022. This led to many western brands suspending operations in Russia, as well as Ukrainien consumers to steer clear of Russian products as a means of hurting Russia economically. According to a study conducted by (Leonidou et al., 2019) amongst 606 Ukrainian consumers aiming to identify personality drivers and behavioral outcomes of consumer animosity, “consumer animosity was found to influence product avoidance, with this association becoming stronger in the case of consumers with higher levels of power distance, uncertainty avoidance, collectivism, and masculinity” (Leonidou et al., 2019). When a consumer’s home country is at war, the most common emotion for the consumer to feel towards the rival country is animosity, which alters the consumers buying behavior into consuming products which were solely manufactured and produced in Ukraine, or were produced from a country which aids Ukraine in the war with Russia. Moreover, when a country, “corporation, or band violates societal norms, consumers tend to become angry and penalize them socially, economically, or politically” (Akhtar et al., 2023). Animosity refers to an individual’s antagonistic feelings towards a hostile country, and can negatively affect consumer buying behavior, as they will begin to boycott products which are manufactured and/or produced in the hostile country. In the case of the Ukraine-Russia conflict, Ukrainian consumers are likely to boycott Russian brands and services as a means of hurting the hostile country economically, with many of the consumers behaving out of animosity towards Russia.

While international animosity towards a hostile country may affect consumer behavior towards foreign and domestic products, domestic conflicts may also alter consumer behavior. In October 2000, Israel had its second Arab Intifada, with violent demonstrations occurring amongst large Arab gatherings within parts of Israel. A study was conducted in 2006 examining Jewish Israelis’ reactions to Arab Israelis’ in the context of consumer behavior towards Arab Israelis’ products and services. The findings of the study suggest that “dogmatism, nationalism, and internationalism predict animosity, which in turn predicts product judgements and buying decisions” (Shoham et al., 2006). One of the limitations of this study is that it is unknown to what extent Jewish Israelis’ consumer behavior is purely indicative of animosity towards Arab Israelis’, and how much of their consumer behavior was dictated by fear. Jewish Israelis living in Israel soon after the second Intifada may have become fearful of entering marketplaces run by Arab Israelis, and may have as a result avoided Arab Israelis’ goods and services for not only animosity, but also fear. During this period, there was a significant decrease in transactions from Jewish Israelis’ towards Arab-Israelis’, mainly as a result of animosity, but also likely out of fear. Consumers will generally change their spending habits as to harm the country or organization the consumer feels threatened by, and these changes in consumer behavior may include boycotting brands from the hostile country, to buying products manufactured and produced in the consumer’s home country.

Changes in consumer behavior are most relevant in everyday purchases such as food purchases, and consumers are likely to notice changes in food prices during periods of conflict between nations. Going back to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while Ukrainian consumers made an effort to avoid Russian products as a means of protest, there was also a decrease in general food consumption as a result of increased food prices. Reduced exports of fertilizer from Russia made food production more costly, leading a sizable portion of the European consumer population to decrease their consumption of food products, as well as an increased proclivity to ration food instead of wasting it. A study conducted in 2023 examined changes in consumer behavior in regards to food amongst 10 European countries following the increase in food prices that came after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with data collected from 6,324 respondents. It was found that “Different strategies were adopted by consumers in reaction to price increases: they buy less, opt for a cheaper brand, shop in a different store, or stop buying certain food products” (Grunert et al., 2023). Moreover, consumption of certain food products decreased, as 36.8% of the respondents reported buying less red meat, and 9.8% of respondents stopped buying alcoholic beverages. The results of the study also found both a trend towards more thriftiness and a trend towards more mindful choices, “and the trend towards more thriftiness is found also among those that change to more mindful food choices” (Grunert et al., 2023). Consumer behavior in terms of food consumption is habitual, as consumers need to consume these products in order to continue living, and disruptive changes in the consumer environment such as war can lead to changes in these habitual behaviors, especially if it’s paired with rising prices.

The results of these studies show that consumers alter their behavior during periods of war, as feelings of nationalism tend to increase in individuals when under threat by another nation. Moreover, everyday consumer purchases tend to reflect underlying beliefs, lifestyle choices, and political biases. A consumer may not be able to stop a rival country with force, but they may be able to hurt the rival nation financially through boycotting certain brands from this rival nation.

Terrorism

The effects of terrorist attacks can be damaging both physically and psychologically to a nation, spreading fear and distrust. It is estimated that since 2000, terrorism has caused around $855 billion dollars in losses. If the analysis is zoomed in to focus on the economic impacts of terrorism, we can see some interesting results. This section aims to analyze and break down how consumer behavior changes before and after acts of terrorism, how much of a lasting effect do these attacks have on a consumer base, and how policy makers adapt to try and fight some of the problems that may arise on economic fronts due to the attack or attacks.

As we know terrorist attacks are swift, without warning and very fear inducing, causing property damage, damage to businesses, fatalities and psychological trauma. We can analyze these impacts through the scope of possibly the most well known act of terror in the modern age, September 11, 2001. Other terror attacks will be analyzed as well to show the impact both short term and long term that a terror attack has on the average consumer such as the Spanish case, where the authors analyze how frequent terrorist attacks around Spain affected consumer behavior.

The paper by Tur-sinai (2014) also shows evidence of a decline in the impact of terrorism on consumer behavior as time passes. This article uses evidence from long-term terror attacks on Israel to unpack the long term effects of terrorism on individuals. The results of the study show that as time goes on, consumers adapt to terror attacks over time. If consumers are initially affected by frequent terror attacks, their behavior will change in the short term. As time progresses however, if they believe that these terror attacks are likely to be a frequent occurrence, consumer tendencies tend to revert back to pre-attack disposition when making choices. It is also interesting to note that when it comes to the consumption of durable vs nondurable goods during the time period of terror attacks differs.

These results coincide with results from Horiachko (2020), which analyzes a consumer’s response.This article presents and identifies some of the main reasons behind what impacts a consumer’s decision to travel to a different destination. The specific models used in the study analyze Ukraine as the country in which people would be traveling to. In this article, the author indicated many factors that go into a consumer’s decision, however this was boiled down to 5 main factors. These factors were then run through a model to test the significance of each factor. The results of the study show 5 main factors that influence someone’s plans to go to a country, those being sensitivity to mass media exposure, the cheapness of the service, social status, perception of terrorism, gender.

Sensitivity to mass media exposure suggests that if people perceive a country as dangerous, tourism will slow down dramatically until deemed less dangerous. Cheapness of service is as the name implies; a person will be more likely to plan a vacation to continue with a planned vacation to a country with terrorism problems if it is cheaper. The results even found that 32% of the respondents would still take a vacation to a dangerous country if it were free. These findings coincide with People with a higher social status are less likely to travel to a country they deem dangerous. A person’s perception of terrorism also plays a large role in the decision an individual makes to travel. If a person believes terrorism is dangerous, they are far less likely to travel to the affected country. The results also showed that gender plays a role in decision making, where women are far less likely to travel to a dangerous country than men.

Roberts (2009) uses the terror attacks that occurred on September 11, as well as previous historical data to gauge the severity that the attack had on the economy. He did this by analyzing forecasts of economic performance before and after the attack, seeing if there was a significant change in consumer behavior. The immediate aftermath of the attack saw an increase in the forecast of unemployment and a forecasted decrease in GDP growth even going into 2002, as is to be expected with a shock that caused so much damage and took so many lives. The results show a somewhat large decline in forecasted GDP immediately following the attack. Terror attacks tend to have a significant effect in the short term, with the government having to react quickly with policy to attempt and combat the shock. There are some long term effects associated with terrorism that government policy has an effect on. An example of this is a “terrorist tax” highlighted by the U.S. Joint Economic Committee (2002), which is not a formal tax set by a government policy, but the result of delays, inefficiencies and frictions caused by terror attacks, which in turn may affect the overall productivity and potential growth rate of the economy. Although a “terrorist tax” is not formally set by the government, there are policies that are enacted that have an effect on the economy.

Security expenditures by the government can be an example of another long term impact of terror attacks. After 9/11, there was an effort to increase security in not only airports, but in general to try and be prepared for another incoming attack. Although a necessary precaution, this moved government spending away from sectors that can be more productive to economic growth such as research and development sectors. This, combined with the actual costs associated with buying new security measures, such as metal detectors and security guards, was thought to have significantly impacted economic growth and productivity. This was due to the regular maintenance that was needed to maintain all of the security measures added, as well as more labor to act as security guards and maintain the machines.

In fact some studies suggest that in the aftermath of a great shock, some economies will actually experience growth. Keeping with 9/11, the immediate aftermath caused property damage, losses in earnings and cleanup costs of between $33-$36 billion dollars (Bram et al., 2002). At the end of 2002 however, the national GDP had increased by 2.7% in the fourth quarter of 2001, and 1% from the end of 2001 to the end of 2002. The increase in growth rate in the final quarter of 2001 indicates the effects of a terror attack on the overall economy is mostly confined to the extremely short term. This is also an indication that in the long term, there is less of an impact on the economy and consumers than in the immediate aftermath of a terror attack, with the 1% increase from the end of 2001 until the end of 2002.

It is clear the impact that a sudden terror attack has on an economy but what about the consumer? Terrorist attacks bring with them loss of life, destruction of property and capital, and psychological damage to the average person. To better understand this, Baumert, Obesso, and Valbuena (2020) help us to unpack the effect terrorism has on a consumer that is a direct victim of terrorism. The experiments performed in this article were meant to try and understand how the victims respond emotionally and behaviorally when given the hypothetical scenario of a plane hijacking in an international airport and compare that to the response of someone who had not experienced a terror attack. The researchers gave both groups 4 different scenarios and asked if plans would be altered if they had news of an impending terror attack.

The results of this experiment show that victims who have been a part of a terror attack are more likely to have a greater fear and think twice about flying, than someone who has not been a victim. Another result from the study also showed that people were less likely to change their plans for a flight for something that has a concrete date such as a friends wedding or job interview, but would be more likely to cancel or change their plans if it was a vacation, most likely due to the fact you can easily choose somewhere else to vacation or choose a different time to go on this vacation. The final results of the study are as follows, “having suffered a terrorist attack makes people perceive a higher level of fear when confronting the possibility of a new attack and increases their sensitivity to the two factors we manipulated in our experiment” (i.e. government response and public reaction). At the same time, it also makes them more cautious and thus more inclined to opt for alternative consumption choices but not to cancel their plans” (Baumert, Obesso, and Valbuena, 2020).

The results of this study match up well with previous studies and literature on the topic, suggesting that terrorist attacks only significantly affect vitamins when it comes to economic decisions in the short run, while it has longer lasting impacts physiologically in the long run.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 epidemic has caused a profound change in consumer behavior and altered how people engage with goods and services during the pandemic. The pandemic brought radical change to the consumption habits of the consumer. Consumers adapted their purchasing patterns, preferences, and priorities in response to COVID-19 such as the panic-buying essential goods to embracing e-commerce and digital services. Yet even with this drastic economic shock from COVID-19 in a couple of months, consumer behavior mostly returned to normal. Thus, COVID-19’s effect on consumer behavior was mostly short-term with little effect on long-term behavior as much of the behavior was driven by government policies such as lockdowns and quarantines.

How a consumer perceives a crisis impacts the consumer’s purchasing behaviors and consumers will develop different behaviors depending on their perception of the crisis (Amalia and Lonut, 2009). The study (Karaboğa, Özsaatc, 2021) aims to find the impact of the crisis perception of COVID-19 on consumer behavior. They achieve this by employing online surveys in Turkey with questions to measure three different consumer attitudes during a crisis. The first attitude is sparingness when consumers will often change their purchasing behaviors to make purchases based on their needs and tend to suppress them more frequently. The second consumer attitude is cautiousness. The third attitude is the concern for the future.

The results of the article state “Based on the sample selected as a result of factor analysis, this scale describes 50.5% of the concept of sparingness 17.2% of the concept of cautiousness, and 15.3% of the concept of concern for the future.”(Karaboğa, Özsaatc, 2021, 748) About half of the participants changed their purchasing behavior to act in a cautious consumption behavior. It could be inferred that consumers’ behaviors could be characterized by a rational choice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rational consumers would choose goods that will provide the highest benefit for them within their limited budget trying to maximize benefit. A key trait for a rational consumer is to behave cautiously rather than spend or save resources. While around only 15% of participants had concerns about the future. Consumers may have perceived the pandemic as a crisis that would not last long and therefore weren’t concerned about the future as much.

The study also found some of the quarantine’s effects on consumer behavior in Turkey. Because the consumer was intensively at home they experienced deductions for various social expenses which created a budget. The budget allowed consumers to allocate to other expenditures such as online shopping. According to the study, consumers who spend the majority of their free time on social media or using electronic devices that display advertisements have ensured that the budget created by the compulsory deductions is channeled toward online shopping (Karaboğa, Özsaatc, 2021).

The study (Küçükkambak, SÜLER, 2022) also studies consumer’s perception of COVID-19 in Turkey. The goal of the study was to see how the pandemic perceived by the consumer impacted whether the consumer engaged in impulsive buying and compulsive buying. Impulsive buying is the act of buying goods and services without planning in advance. While compulsive buying is an incessant need to buy goods and services. The study found that consumers engage more in impulsive buying tendencies compared to compulsive buying tendencies during COVID-19 (Küçükkambak, SÜLER, 2022). They found that those who prefer shopping online had higher total compulsive and impulsive buying behaviors than consumers who prefer shopping in person (Küçükkambak, SÜLER, 2022). The study also found that education impacted consumer behavior as consumers with primary education levels had lower rates of impulsive buying behaviors compared to consumers with higher education levels(Küçükkambak, SÜLER, 2022).

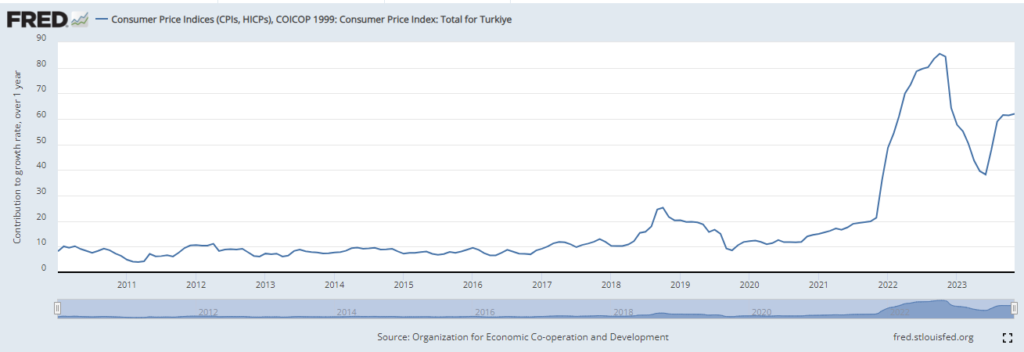

Figure 1 illustrates s Turkey’s consumer price index total throughout the years. Viewing the years in which COVID-19 started December 2019 through June 2020 when Turkey reopens there are no noticeable changes to the graph with the only exception of April 2020 which shows a slight dip but quickly resorts in the following month. Despite the rapid changes in consumer behavior, the effect it had on the consumer price index was minimal in the short run.

The article by (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022) looks into the effects quarantine had on consumer behavior. The authors achieve this by evaluating food prices and consumption of food products in China. China’s local pandemic policies, namely health emergency declarations, and lockdowns directly affected consumer behavior (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022). The average food prices rise by 7.8 standard deviations of the price change distribution during COVID-19 (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022). Non‐perishable vegetables, such as Chinese cabbage and potato with the most heavily affected group of food which impacted the consumer well-being negatively as Chinese households consume twice as many vegetables as meat and fruit, and they also spend a large percentage of their food budget on them (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022). The demand shock to food prices especially impacted lower-income households as they spend higher portions of their food budgets on vegetables compared to higher-income households who spend more money on meat (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022).

In China, emergency declarations and lockdown policies were decentralized thus lockdown strictness depended on the province and had varying lockdown strictness and timing. The authors state “Of the 48 cities that imposed lockdowns, 22 restricted visitors to residential communities and required residents to enter or exit with valid IDs. The remaining 26 cities enforced de facto house arrests and allowed only one person per household to leave their homes to shop every day or every other day.”(Yang, Asche, Li, 2022, p.1442) Cities that were faced with harsher lockdowns such as only allowing one person per household to leave their homes were faced with non‐perishable prices that were 14.7% higher than their levels in 2019 (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022). Compared to cities with loose lockdowns only suffering from modest price changes to non‐perishable food products. Perhaps consumers who faced harsher lockdowns felt a greater need to stockpile food for home consumption due to being less likely to leave their homes.

Emergency declarations were generally announced well before lockdowns with an average difference of 12.3 days (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022). The declarations led many consumers to engage in panic buying mainly of non‐perishable food items, potentially due to concerns about future shortages. Panic buying led to increased demand for non-perishable food items and thus a price increase. The demand shock was short-lived as consumers soon realized most food items were still available (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022). Emergency declarations had more effect on the increase in food prices but were more short-lived while under lockdowns there was a sustained increase in demand for non‐perishable (Yang, Asche, Li, 2022).

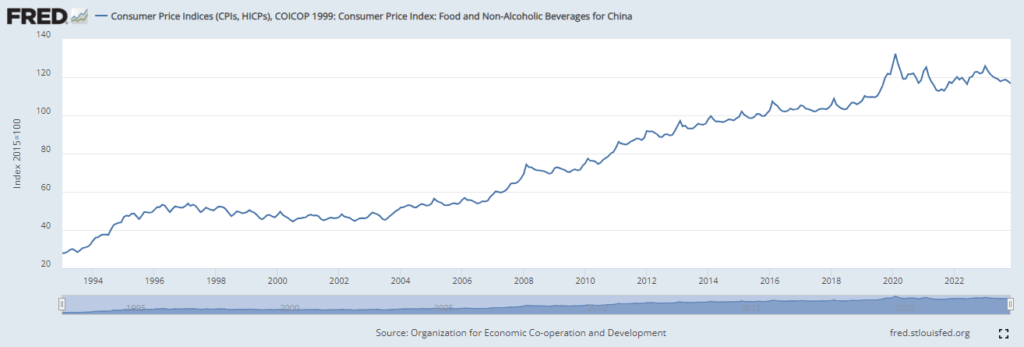

Figure 2 illustrates the consumer price index of food and non-alcoholic beverages in China. The first case of COVID-19 happened in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. When viewing the graph there is an increase in the consumer price index in December 2019 where it peaked in February 2020 yet in the subsequent months the consumer price index decreases. The decrease is mostly due to the cities’ loosened restrictions and lifting lockdowns. Thus showcasing the short-term effect COVID-19 had on consumer behavior.

Many industries were affected by the pandemic across the world including alcohol. Wine is a huge cultural part of a nation, especially in Europe. The article (Dubois et al, 2021) aims to study the consumer behavior of alcohol during COVID-19. The study focuses on the research of the nations of France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal and whether the lockdowns led to a change in the frequency of the consumption of wine. The nations have cultural similarities when it comes to wine and are large consumers of it. The authors used online surveys to ask consumers about consumer consumption and purchasing habits of wine and other alcoholic beverages (beer and spirits) before and during the lockdown; possible economic, emotional, and psychological effects of the lockdown; and sociodemographic variables.

The study showed that during the lockdowns wine consumption frequency increased with it being more than other alcoholic beverages in each of the countries (Dubois et al, 2021). While the frequency of the consumption of spirits was significantly less common everywhere except for those living abroad (Dubois et al, 2021). Increased beer consumption was significantly more frequent than spirits except in Portugal and for foreigners (Dubois et al, 2021). The study also showed a substitution between alcoholic beverages everywhere but found a loyalty of wine consumers to wine, and those who increased their consumption frequency also increased its quality (Dubois et al, 2021).

Various factors affect the consumer’s behavior toward alcohol. The study shows that household size had a positive effect observed in France and Italy on the consumption of wine but whether it was older kids returning home or younger children encouraging parents to drink more is yet to be seen (Dubois et al, 2021). All age categories significantly correlated to an increase in wine consumption frequency, and the older the respondents, the lower the probability of reduced consumption (Dubois et al, 2021). Gender was shown to have a negative effect on the consumption of wine where males consumed wine less often during the lockdown (Dubois et al, 2021). Only in France did income levels significantly affect consumption with the lowest incomes increasing their wine consumption (Dubois et al, 2021).

COVID-19 was an unprecedented economic crisis that took many nations by surprise. The uncertainty surrounding health, employment, and the economy led to significant shifts in consumption patterns. Such as consumers becoming more engaged with cautious behavior patterns while at the same time becoming more impulsive buyers with the shift to online shopping. How the government responded to COVID-19 also shaped how the consumers responded as the implementation of quarantine and emergency declarations led consumers to panic buying. Yet in the long run, COVID-19 wasn’t effective as many consumers were driven by the policies of their government thus when the restrictions were lifted consumer behavior returned mostly to normal.

The 2008 Financial Crisis

Financial Crisis like the one in 2008 are quick panics where people can experience massive shifts in perceived and real economic conditions. As discussed earlier, this chapter intends to find similarities between consumer behavior in different types of crises and furthermore will be exploring the 2008 financial crisis specifically. In 2008, banks were giving out sub-prime rate and adjustable mortgages to keep up with the massive inflow of people who recently acquired money during the Dot-com bubble. The sub-prime rates were set very low to cover the exploding market for new homes but as the economy kept growing, these rates began to increase. Subsequentily many people were not able to cover the new interest rates so mortgages started to default at a rapid rate. This caused many property owners to sell to cover their loss, leading to a chain of events which resulted in the bursting of the housing bubble (The Investopedia Team, 2023).

Following the burst of the housing bubble many banks and financial institutions in the U.S. and around the globe experienced liquidity problems. Many people wanted to make a run on the banks fearing another great depression, this led to banks being more tight with their lending policy which has many effects on economic conditions across the country (Mehidian, 2019). Based on basic economic theory, With higher interest rates, unemployment should rise as they are directly related. Subsequently, over eight million establishment jobs were lost during the recession (Connaughton, 2012), raising the unemployment rate to 6.9 percent, the largest increase since 1982 as seen in figure 1 (Borbely, 2009). While unemployment increased, the labor force participation rate remained relatively unchanged which indicates that the reason there was a downturn in the labor market was mostly due to people losing jobs. Although, unemployment was not uniform across all states. Nevada, Arizona and Florida were hit the hardest with an employment loss of roughly 11% versus North Dakota which actually had an employment increase of 1.24% (Connaughton, 2012).

With these drastic economic conditions, changes in spending patterns will develop in consumers. “…Economic landscape had a profound impact on consumers. New appetites emerged, and markets sprang up to serve them” (Flatters, 2009, p. 1) In the years leading up to the recession, consumers were simplifying their spending and focusing on products that were easy to get and simple to use. As the recession kicked into high gear, consumers wanted to simplify their life even more and not have to hassle for things as things. Consumers got more thrifty as research conducted by Harvard suggests that people had a mounting dissatisfaction with excessive consumption and desired a less wasteful life. This is a result of economic conditions as when unemployment is high people spend less fearing worsening conditions of the economy (Flatters, 2009). Other luxury goods like products bought for ethical reasons and extreme-thrill seeking goods had the biggest hit on spending. The recession had such a hit on luxury spending that even former President Barack Obama noted in 2009 that he believed it was unlikely that the U.S. would reemerge back to its former high spending market (Flatters, 2009).

Green consumerism also takes a big hit as people shrink their capacity to spend more money. Just as luxury goods became less attractive, environmentally friendly products were not seen as worth the extra penny. Spending was tightening and consumers did not see it being worth their valuable money. Specifically, spenders cut back on products that boost their green credentials, which are premium green products bought with the hope of boasting the individual’s consciousness of the planet (Flatters, 2009).

The consumption and sale of beer can be used as a good indicator for economic conditions as many people see it as a normal good, so spending levels should not drop drastically in a recession. A study done by Joseph W. Gilkey Jr. and Sylvia D. Clark set out to use beer sales as a tool to judge consumer spending habits during the 2008 Recession. They use the reasoning, “Beer is a highly visible product when served by consumers to friends, family and guests in their homes or in restaurants, bars, clubs and taverns. The visibility impact of this product can enhance market pressures on the quality beer product, especially with regard to the desire to be viewed as converting positive attributes of consumer status and perception” (Gilkey Jr, 2015, p. 3). By assuming that people use beer and alcohol to demonstrate their class to their peers, we can make inferences about consumer spending reasonings. The data found by Gilkey and Clark suggests that consumers wanted to entertain guests at home instead of private establishments due to spending constraints but still spent money on higher value alcohol as they still valued perceptions of wealth from their peers (Gilkey Jr, 2015).

“The financial crisis has put a spotlight on corporate governance, in particular the malfeasance of some executives and the complicity of their companies’ boards” (Flatters, 2009, p. 1). This recession in particular put a big spotlight on big corporations and their inner workings. The reason for the recession was ignorance on the corporate level and the public knows this, causing a lot of distrust and anger for big firms and especially Wall street. The public’s reflex for punishing mismanaged and corrupt companies is not just because of the 2008 recession but stems from something much deeper that has been around for years such as the Enron and WorldCom scandals of 2001. But this distrust grew in 2008 as the government stepped in and gave out large corporate bailouts to big companies. The public saw this as a stab in the back as the companies that were ignorant and fraudulent were getting bailed out as the average joe was getting laid off (Flatters, 2009). There have been countless movies created about the recession and specifically the corporate bailouts, and none of them have painted a positive picture of big companies.

As financial crisis’s put a lot of strain on government and financial institutions, understanding how they dealt with the recession will give an insight on consumer behavior as financial institutions use interest rates to reach their targets. These changing interest rates affect all aspects of an economy and can dictate how consumers spend their money.

Overall, bank efficiency took a hit during the recession. Just like consumers, banks became more risk averse. This led them to make investments with a lower yield as they would not accept the risk of an investment with a higher yield. This was especially evident in the housing market, where banks chose to take a much lower position on them than before the recession. This is due to the recession being caused by unstable rates for mortgages resulting in an overall distrust in the housing market. Efficiency also takes a hit from the high unemployment rate in the job market. Less full time employees equates to less work being done per hour (Mehdian, 2019).

Consumers during the 2008 financial crisis experienced increasing prices and increasing unemployment which both affected their spending. People became more tight with their money as there was a growing uncertainty about future economic conditions. This was made worse by distrust and anger directed towards big companies and financial institutions that were at fault for the recession. All of this combined with banks being more risk averse and less effiecent leads to consumers tightening up their budgets and holding more in cash.

Conclusion

Our findings show that although demand shocks do in fact have a large impact on consumers, this is almost all in the short run. As time goes on, consumer behavior smooths out, often returning the same type and level of spending as was occurring before the shock. Most of the long-term effects of a shock are felt on a psychological level, as people who have been directly affected by a shock may change a consumer’s attitude towards spending, saving, and decision-making.

References

Akhtar, N., Khan, H., Siddiqi, U. I., Islam, T., & Atanassova, I. (2024). Critical perspective on consumer animosity amid Russia-Ukraine war. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 20(1), 49-70.

Bardwell Harrison & Iqbal Mohib, 2021. “The Economic Impact of Terrorism from 2000 to 2018,” Peace Economics, Peace Science, and Public Policy, De Gruyter, vol. 27(2), pages 227-261, May.

Baumert, Thomas & de Obesso, María Mercedes & Valbuena, Esther, 2020. “How does the terrorist experience alter consumer behaviour? An analysis of the Spanish case,” Journal of Business Research, vol. 115(C), pages 357-364.

Borbely, J. M. (2009). US labor market in 2008: Economy in recession. Monthly Lab. Rev., 132, 3.

Bram, J., Orr, J., & Rapaport, C. (n.d.). Measuring the effects of the September 11 attack on New York City. https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/epr/02v08n2/0211rapa/0211rapa.html#:~:text=Adding%20up%20the%20earnings%20and,%2433%20billion%20and%20%2436%20billion.

Chavis, L., & Leslie, P. (2009). Consumer boycotts: The impact of the Iraq war on French wine sales in the US. QME, 7, 37-67.

Connaughton, J. E., & Madsen, R. A. (2012).US state and regional economic impact of the 2008/2009 recession. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy,

42(1100-2016-90101).

CİCİ, E. N., & ÖZSAATCI, F. G. B. (2021). The impact of crisis perception on consumer purchasing behaviors during the COVID-19 (coronavirus) period: a research on consumers in Turkey. Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, 16(3), 727-754.

Dolfman, M.L. & Wasser, S.F. & Skelly, Katherine. (2006). Structural changes in Manhattan’s post-9/11 economy. 129. 58-79. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2006/10/art4full.pdf

Dubois, M., Agnoli, L., Cardebat, J. M., Compés, R., Faye, B., Frick, B., … & Simon-Elorz, K. (2021). Did wine consumption change during the COVID-19 lockdown in France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal? Journal of Wine Economics, 16(2), 131-168.

Flatters, P., & Willmott, M. (2009). Understanding the post-recession consumer. Harvard Business Review, 87(7/8), 106-112.

Gilkey Jr, J. W., & Clark, S. D. (2015). The 2008 Global Financial Crisis Post-Recession Impact on Consumer Behavior Based on Educational Level. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology, 6(6), 363-366.

Grunert, K. G., Chimisso, C., Lähteenmäki, L., Leardini, D., Sandell, M. A., Vainio, A., & Vranken, L. (2023). Food-related consumer behaviours in times of crisis: Changes in the wake of the Ukraine war, rising prices and the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Research International, 173, 113451.

Helms, B., Pandya, S. S., & Venkatesan, R. (2021). War on Aisle 5: Casualties, National Identity, and Consumer Behavior. Journal of Conflict Resolution

Horiachko, K. (2020). Research of the impact of the terrorism and other factors on the consumers behavior. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 7, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v7i1.433

Kirchler, E., & Hoelzl, E. (2015). Economic and psychological determinants of consumer behavior. Zeitschrift für Psychologie.

Klein, Lawrence R. and Ozmucur, Suleyman (2002) “Consumer Behavior Under the Influence of Terrorism Within the United States,” Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance and Business Ventures. Vol. 7: Iss. 3, pp. 1-16.

Küçükkambak, S. E., & Süler, M. (2022). The Mediating Role of Impulsive Buying in The Relationship Between Fear of COVID-19 and Compulsive Buying: A Research on Consumers in Turkey. Sosyoekonomi, 30(51), 165-197. https://doi.org/10.17233/sosyoekonomi.2022.01.09

Leonidou, L. C., Kvasova, O., Christodoulides, P., & Tokar, S. (2019). Personality traits, consumer animosity, and foreign product avoidance: The moderating role of individual cultural characteristics. Journal of International Marketing, 27(2), 76-96.

Mehdian, S., Rezvanian, R., & Stocia, O. (2019). The Effect of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis on the Efficiency of Large U.S. Commercial Banks. Review of Economic and Business Studies, 12(2), 11-27.

Pandelica Ionut, & Pandelica Amalia. (2009). CONSUMERS’ REACTION AND ORGANIZATIONAL RESPONSE IN CRISIS CONTEXT. Analele Universităţii din Oradea. Ştiinţe economice, 4(1), 779–782.

Roberts, B. W. (2009). The macroeconomic impacts of the 9/11 attack: Evidence from real-time forecasting. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.2202/1554-8597.1166

Shoham, A., Davidow, M., Klein, J. G., & Ruvio, A. (2006). Animosity on the home front: The Intifada in Israel and its impact on consumer behavior. Journal of International marketing, 14(3), 92-114.

Tur-sinai, A. (2014). Adaptation patterns and consumer behavior as a dependency on terror Mind & Society, 13(2), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11299-014-0154-8

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE, April 26, 2024.

U.S. Joint Economic Committee. (2002, May). The Economic Costs of Terrorism. https://www.jec.senate.gov/ https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/79137416-2853-440b-9bbe-e1e75d40a79d/the-economic-costs-of-terrorism—may-2002.pdf

Yang, B., Asche, F., & Li, T. (2022). Consumer Behavior and Food Prices during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Chinese Cities. Economic Inquiry, 60(3), 1437–1460.

2008 Recession: What it Was and What Caused It. (2023, 12 18). Investopedia. Retrieved March 18, 2024, from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/great-recession.asp

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Consumer Price Indices (CPIs, HICPs), COICOP 1999: Consumer Price Index: Total for Turkiye [TURCPALTT01CTGYM], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TURCPALTT01CTGYM, May 3, 2024.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Consumer Price Indices (CPIs, HICPs), COICOP 1999: Consumer Price Index: Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages for China [CHNCP010000IXOBM], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CHNCP010000IXOBM, May 2, 2024.

Appendix

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3: